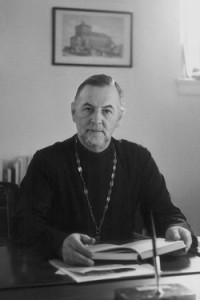

Alexander Schmemann

When a man leaves on a journey, he must know where he is going. Thus with Lent. Above all, Lent is a spiritual journey and its destination is Easter, “the Feast of Feasts.” It is the preparation for the “fulfillment of Pascha, the true Revelation.” We must begin, therefore, by trying to understand this connection between Lent and Easter, for it reveals something very essential, very crucial about our Christian faith and life.

Is it necessary to explain that Easter is much more than one of the feasts, more than a yearly commemoration of a past event? Anyone who has, be it only once, taken part in that night which is “brighter than the day,” who has tasted of that unique joy, knows it. On Easter we celebrate Christ’s Resurrection as something that happened and still happens to us. For each one of us received the gift of that new life and the power to accept it and live by it. It is a gift which radically alters our attitude toward everything in this world, including death. It makes it possible for us to joyfully affirm: “Death is no more!” Oh, death is still there, to be sure, and we still face it and someday it will come and take us. But it is our whole faith that by His own death Christ changed the very nature of death, made it a passage — a “passover,” a “Pascha” — into the Kingdom of God, transforming the tragedy of tragedies into the ultimate victory.

Such is that faith of the Church, affirmed and made evident by her countless Saints. Is it not our daily experience, however, that this faith is very seldom ours, that all the time we lose and betray the “new life” which we received as a gift, and that in fact we live as if Christ did not rise from the dead, as if that unique event had no meaning whatsoever for us? We simply forget all this — so busy are we, so immersed in our daily preoccupations — and because we forget, we fail. And through this forgetfulness, failure, and sin, our life becomes “old” again — petty, dark, and ultimately meaningless — a meaningless journey toward a meaningless end. We may from time to time acknowledge and confess our various “sins,” yet we cease to refer our life to that new life which Christ revealed and gave to us. Indeed, we live as if He never came. This is the only real sin, the sin of all sins, the bottomless sadness and tragedy of our nominal Christianity.

If we realize this, then we may understand what Easter is and why it needs and presupposes Lent. For we may then understand that the liturgical traditions of the Church, all its cycles and services, exist, first of all, in order to help us recover the vision and the taste of that new life which we so easily lose and betray, so that we may repent and return to it. And yet the “old” life, that of sin and pettiness, is not easily overcome and changed. The Gospel expects and requires from man an effort of which, in his present state, he is virtually incapable. This is where Great Lent comes in. This is the help extended to us by the Church, the school of repentance which alone will make it possible to receive Easter not as mere permission to eat, to drink, and to relax, but indeed as the end of the “old” in us, as our entrance into the “new.” For each year Lent and Easter are, once again, the rediscovery and the recovery by us of what we were made through our own baptismal death and resurrection.

A journey, a pilgrimage! Yet, as we begin it, as we make the first step into the “bright sadness” of Lent, we see — far, far away — the destination. It is the joy of Easter, it is the entrance into the glory of the Kingdom. And it is this vision, the foretaste of Easter, that makes Lent’s sadness bright and our lenten effort a “spiritual spring.” The night may be dark and long, but all along the way a mysterious and radiant dawn seems to shine on the horizon. “Do not deprive us of our expectation, O Lover of man!” Glory be to God!